Dean Acheson

| Dean Gooderham Acheson | |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office January 21, 1949 – January 20, 1953 |

|

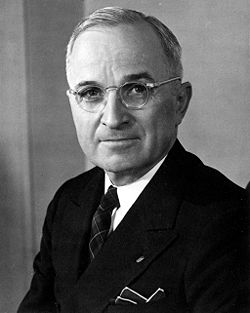

| President | Harry Truman |

| Preceded by | George Marshall |

| Succeeded by | John Foster Dulles |

|

|

|

| Born | April 11, 1893 Middletown, Connecticut United States |

| Died | October 12, 1971 (aged 78) Sandy Spring, Maryland United States |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Alice Stanley |

| Children | David Acheson Jane Acheson Mary Acheson |

| Alma mater | Yale College Harvard Law School |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Religion | Episcopalian |

| Military service | |

| Service/branch | United States National Guard |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

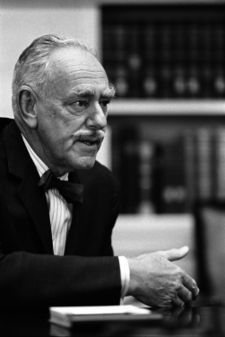

Dean Gooderham Acheson (April 11, 1893 – October 12, 1971) was an American statesman and lawyer; as United States Secretary of State in the administration of President Harry S. Truman during 1949–1953, he played a central role in defining American foreign policy during the Cold War.[1] One historian writes, "Dean Acheson was more than 'present at the creation' of the Cold War; he was a primary architect."[2] Specifically, Acheson played a central role in the creation of such institutions and policies as the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Acheson's most famous decision was convincing President Truman to intervene, in June 1950, in the Korean War. He also persuaded Truman to dispatch aid and advisors to French forces in Indochina, though in 1968 he finally counseled President Lyndon B. Johnson to negotiate for peace with North Vietnam. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, President John F. Kennedy called upon Acheson for advice, bringing him into the executive committee (ExComm), a strategic advisory group.

Acheson came under heavy attack for his policies in China and for his defense of State Department employees (such as Alger Hiss) accused during the anti-Communist Red Scare investigations of Senator Joseph McCarthy and others.

Contents |

Early life and career

Dean Acheson was born in Middletown, Connecticut. His father, Edward Campion Acheson, was an English-born Church of England priest who, after several years in Canada, moved to the U.S. to become Episcopal Bishop of Connecticut. His mother, Eleanor Gertrude Gooderham, was a granddaughter of prominent Canadian distiller William Gooderham (1790–1881), founder of the Gooderham and Worts Distillery. Like his father, he was a staunch Democrat and opponent of prohibition.

Acheson attended Groton School and Yale College (1912–1915), where he joined Scroll and Key Society, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa[3] and was a brother of the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity (Phi chapter). At Groton and Yale he had the reputation of a partier and prankster; he was somewhat aloof but still popular with his classmates. Acheson's well-known, reputed arrogance—he disdained the curriculum at Yale as focusing on memorizing subjects already known or not worth knowing more about—was early apparent. At Harvard Law School from 1915 to 1918, however, he was swept away by the intellect of professor Felix Frankfurter and finished fifth in his class, while rooming with songster Cole Porter.

During wartime service in the National Guard, in 1917 he married Alice Stanley. She loved painting and politics and served as a stabilizing influence throughout their enduring marriage; they had three children: David, Jane, and Mary. At that time, a new tradition of bright law students clerking for the U.S. Supreme Court had been begun by Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, for whom Acheson clerked for two terms from 1919 to 1921. Frankfurter and Brandeis were close associates, and future Supreme Court Justice Frankfurter suggested that Brandeis take on Acheson.[4]

Economic diplomacy

A lifelong Democrat, Acheson worked at a law firm in Washington D.C., Covington & Burling, often dealing with international legal issues before Franklin Delano Roosevelt appointed him Undersecretary of the United States Treasury in 1933. When Secretary William H. Woodin fell ill, Acheson suddenly found himself acting secretary despite his ignorance of finance. Because of his opposition to FDR's plan to inflate the dollar by controlling gold prices, he was forced to resign in November 1933 and resumed his law practice.[5] In 1939-1940 he headed a committee to study the operation of administrative bureaus in the federal government.

World War II

FDR brought Acheson back as assistant secretary of state in 1941, where he developed much of the economic warfare waged by the United States against the Axis Powers.[6] He designed the American/British/Dutch oil embargo that cut off 95 percent of Japanese oil supplies and escalated the crisis with Japan in 1941. Historians debate whether Roosevelt fully understood and approved the scope of the embargo, but there is no doubt Acheson knew it could produce war.[7]

Postwar planning

In 1944, Acheson attended the Bretton Woods Conference as the head delegate from the State department. At this conference the post-war international economic structure was designed. The conference was the birthplace of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the last of which would evolve into the World Trade Organization.

Cold War diplomacy

Later, in 1945, Harry S. Truman selected Acheson as his Undersecretary of United States Department of State; he retained this position working under Secretaries of State Stettinius, Byrnes, and Marshall.

As late as 1945 Acheson sought détente with the Soviet Union. In 1946, as chairman of a special committee to prepare a plan for the international control of atomic energy, he wrote the Acheson-Lilienthal report. At first Acheson was conciliatory towards Stalin. The Soviet Union's attempts at regional hegemony in Eastern Europe and in Southwest Asia, however, changed his thinking. When he realized the Soviets were working outside traditional diplomatic channels, Acheson became a devoted and influential cold warrior.[8] The Secretary was often overseas, making Acheson acting Secretary. During this period, Acheson cemented a close relationship with President Truman. Acheson devised the policy and wrote Truman's 1947 request to Congress for aid to Greece and Turkey, a speech which stressed the dangers of totalitarianism rather than Soviet aggression and marked the fundamental change in American foreign policy that became known as the Truman Doctrine.[9] Acheson designed the economic aid program to Europe that became known as the Marshall Plan. Acheson believed the best way to contain Stalin's Communism and prevent future European conflict was to restore economic prosperity to Western Europe, to encourage interstate cooperation there, and to help the American economy by making its trading partners richer.

In 1949, Acheson was appointed Secretary of State. In this position he built a working framework for containment, first formulated by George Kennan, who served as the head of Acheson's Policy Planning Staff. Acheson was the main designer of the military alliance NATO, and signed the pact for the United States. The formation of NATO was a dramatic departure from historic American foreign policy goals of avoiding any "entangling alliances."

The White Paper Defense

During the summer of 1949 the state department, headed by Acheson, produced a study of recent Sino-American relations. The document known officially as United States Relations with China with Special Reference to the Period 1944-1949, which later was simply called the China White Paper, attempted to dismiss any misinterpretations of Chinese and American diplomacy toward each other.[10] Published during the height of Mao Zedong's takeover, the 1,054 page document argued that American intervention in China was doomed to failure. Although Acheson and Truman had hoped that the study would dispel rumors and conjecture,[11] the paper helped to convince many critics that the administration had indeed failed to check the spread of communism in China.[12]

Korean war

Acheson's speech on January 12, 1950, before the National Press Club [13] seemed to say that South Korea was beyond the American defense line and that American support for the new Syngman Rhee government in South Korea would be limited. Critics later charged that Acheson's ambiguity provided Joseph Stalin and Kim Il-sung with reason to believe the US would not intervene if they invaded the South. However, evidence from Korean and Soviet archives demonstrates that Stalin and Kim's decisions were not influenced by Acheson's speech.[14]

Partisan attacks

With the Communist takeover of mainland China in 1949, that country switched from a close friend of the U.S. to a bitter enemy—the two powers were at war in Korea by 1950. Critics blamed Acheson for what they called the "loss of China" and launched several years of organized opposition to Acheson's tenure; Acheson ridiculed his opponents and called this period in his outspoken memoirs "The Attack of the Primitives." Although he maintained his role as a firm anti-communist, he was attacked by various anti-communists for not taking a more active role in attacking communism abroad and domestically, rather than hew to Acheson's policy of containment of communist expansion. Both he and Secretary of Defense George Marshall came under attack from men such as Joseph McCarthy; Acheson became a byword to some Americans, who tried to equate containment with appeasement. Congressman Richard Nixon, who later as President would call on Acheson for advice, ridiculed "Acheson's College of Cowardly Communist Containment." This criticism grew very loud after Acheson refused to 'turn his back on Alger Hiss' when the latter was accused of being a Communist spy, and convicted (of perjury for denying he was a spy).

On December 15, 1950, the Republicans in the House of Representatives resolved unanimously that he be removed from office, to no avail.

Return to private life

He retired as secretary of state on Jan. 20, 1953, and served on the Yale Board of Trustees along with Senator Robert A. Taft, one of his sharpest critics.

Acheson returned to his private law practice. Although his official governmental career was over, his influence was not. He was ignored by the Eisenhower administration but headed up Democratic Policy Groups in the late 1950s. Much of President John F. Kennedy's flexible response policies came from the position papers drawn up by this group.

Acheson's law offices were strategically located a few blocks from the White House and he accomplished much out of office. He became an unofficial advisor to the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, for example, he was dispatched by Kennedy to France to brief French President Charles de Gaulle and gain his support for the United States blockade.

During the 1960s, he was a leading member of a bipartisan group of establishment elders known as The Wise Men who initially supported the Vietnam War but then turned against it at a critical meeting with President Lyndon Johnson in March 1968. He reconciled with his old foe Richard Nixon and quietly became a major advisor to President Nixon.

In 1964, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In 1970, he won the Pulitzer Prize for History for his memoirs of his tenure in the State Department, Present at the Creation: My Years in the State Department. The Modern Library placed the book at #47 on its top 100 non-fiction books of the 20th century.[15]

In 1971, Dean Acheson died of a massive stroke at his farm in Sandy Spring, Maryland at the age of 78. He was survived by a son, David C. Acheson, and a daughter, Mary Acheson Bundy, wife of William P. Bundy.

Notes

- ↑ Chambers Biographical Dictionary, ISBN 0-550-18022-2, page 6

- ↑ Randall Bennett Woods, "The Good Shepherd," Reviews in American History, Volume 35, Number 2, June 2007, pp. 284-288

- ↑ Brennan, Elizabeth A., Clarage, Elizabeth C.Who's who of Pulitzer Prize winners, Greenwood, 1999, p. 290

- ↑ Beisner (2006)

- ↑ Acheson explained his opposition to this plan, and described his experience as Treasury Undersecretary in the chapter "Brief Encounter — With FDR" in his 1965 memoir Morning and Noon (pp. 161–194).

- ↑ Perlmutter, Oscar William (1961). "Acheson and the Diplomacy of World War II". The Western Political Quarterly 14 (4): 896–911. doi:10.2307/445090.

- ↑ Irvine H. Anderson, Jr., "The 1941 De Facto Embargo on Oil to Japan: A Bureaucratic Reflex," The Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 44, No. 2. (May, 1975), pp. 201-231. in JSTOR

- ↑ Beisner (1996)

- ↑ Frazier 1999

- ↑ Robert Garson, "The United States and China since 1949," (1994) pp. 27-33

- ↑ Lewis McCarroll Purifoy, "Harry Truman's China Policy," (1976) pp. 125-150

- ↑ Neil L. O'Brien, "An American Editor in Early Revolutionary China," (2003) pp. 169-170

- ↑ Excerpts

- ↑ David S. McLellan, "Dean Acheson and the Korean War," Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 83, No. 1 (Mar., 1968), pp. 16-39 in JSTOR

- ↑ http://www.randomhouse.com/modernlibrary/100bestnonfiction.html

References

- Acheson, Dean (1965). Morning and Noon: A Memoir. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Beisner, Robert L. Dean Acheson: A Life in the Cold War. (2006), 800 pp

- Beisner, Robert L. "Patterns of Peril: Dean Acheson Joins the Cold Warriors, 1945-46." Diplomatic History 1996 20(3): 321-355. Issn: 0145-2096 Fulltext: in Swetswise and Ebsco

- Brinkley, Douglas. Dean Acheson: The Cold War Years, 1953-71. 1992. 429 pp.

- Brinkley, Douglas, ed. Dean Acheson and the Making of U.S. Foreign Policy. 1993. 271 pp. essays by scholars

- Chace, James. Acheson: The Secretary of State Who Created the American World. (1998). 512 pp.

- Frazier, Robert. "Acheson and the Formulation of the Truman Doctrine." Journal of Modern Greek Studies 1999 17(2): 229-251. Issn: 0738-1727 in Project Muse

- Garson, Robert. "The United States and China since 1949: A Troubled Affair." Fairleigh Dickinson U. Press, Madison, 1994: pp. 27-33 ISBN 0-8386-3610-1

- Goulden, Joseph C. (1971). The Superlawyers: The Small and Powerful World of the Great Washington Law Firms. New York: Weybright and Talley.

- Harper, John Lamberton. American Visions of Europe: Franklin D. Roosevelt, George F. Kennan, and Dean G. Acheson. Cambridge U. Press, 1994. 378 pp.

- Kaplan, Lawrence S. The Long Entanglement: NATO's First Fifty Years (1999) online edition

- Isaacson, Walter, and Evan Thomas. The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made (1997) 864pp; covers Acheson and colleagues Charles E. Bohlen, W. Averell Harriman, George Kennan, Robert Lovett, and John J. McCloy; excerpt and text search

- Leffler, Melvyn P. "Strategy, Diplomacy, and the Cold War: the United States, Turkey, and NATO, 1945-1952" Journal of American History 1985 71(4): 807-825. in JSTOR* McGlothlen, Ronald L. Controlling the Waves: Dean Acheson and US Foreign Policy in Asia (1993) online edition

- McLellan, David S. "Dean Acheson and the Korean War," Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 83, No. 1 (Mar., 1968), pp. 16-39 in JSTOR

- McNay, John T. Acheson and Empire: The British Accent in American Foreign Policy (2001) online edition

- Merrill, Dennis. "The Truman Doctrine: Containing Communism and Modernity" Presidential Studies Quarterly 2006 36(1): 27-37. online edition at Blackwell Synergy

- O'Brien, Neil L. "An American Editor in Early Revolutionary China: John William Powell and the China Weekly/Monthly Review." Routledge, New York, 2003: pp. 169-170 ISBN 0-415-94424-4

- Offner, Arnold A. "'Another Such Victory': President Truman, American Foreign Policy, and the Cold War." Diplomatic History 1999 23(2): 127-155. online in Blackwell Synergy

- Offner, Arnold A. Another Such Victory: President Truman and the Cold War. (2002) 640pp, highly negative excerpts and text search

- Perlmutter, Oscar William. "The 'Neo-Realism' of Dean Acheson," The Review of Politics, Vol. 26, No. 1 (Jan., 1964), pp. 100-123 in JSTOR

- Perlmutter, Oscar William. "Acheson and the Diplomacy of World War II," The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Dec., 1961), pp. 896-911 in JSTOR

- Purifoy, Lewis McCarroll. "Harry Truman's China Policy." Franklin Watts, New York, 1976: pp. 125-150 ISBN 0-531-05386-5

- Spalding, Elizabeth Edwards. The First Cold Warrior: Harry Truman, Containment, and the Remaking of Liberal Internationalism (2006)

Primary sources

- Acheson, Dean. A Democrat Looks at His Party (1955)

- Acheson, Dean. A Citizen Looks at Congress (1957)

- Acheson, Dean. Sketches from Life of Men I Have Known (1961)

- Acheson, Dean (1965). Morning and Noon: A Memoir. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Acheson, Dean (1969). Present at the Creation: My Years in the State Department. New York: Norton. pp. 798 pp. ASIN B0006D5KRE. highly revealing memoir; won the Pulitzer prize; excerpt and text search

- Acheson, Dean. The Korean War (1971),

- Acheson, Dean (1971). Fragments of My Fleece. New York: Norton. pp. 222 pp.

- McLellan, David S., and David C. Acheson, eds. Among Friends: Personal Letters of Dean Acheson (1980)

External links

- Work on Acheson's Role in Designing the Foreign Policy Stance of the Democratic Party after the 1952 election.

- Annotated bibliography for Dean Acheson from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Joseph C. Grew |

Under Secretary of State 1945 – 1947 |

Succeeded by Robert A. Lovett |

| Preceded by George C. Marshall |

United States Secretary of State Served under: Harry S. Truman 1949–1953 |

Succeeded by John Foster Dulles |

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||